When Cancer Can’t Escape

If we were to present her research as an action movie plot, this is how Kate Rittenhouse-Olson and her team at the University at Buffalo plan to beat cancer:

If we were to present her research as an action movie plot, this is how Kate Rittenhouse-Olson and her team at the University at Buffalo plan to beat cancer:

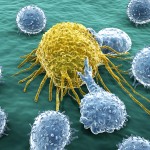

A SWAT team of engineered antibodies hunts down cancer tumors where they live, secures the perimeter so they can’t escape and then busts down the door and delivers a fatal dose of chemicals to finish the job, with no civilian casualties.

In a few years, this show could be playing in patients everywhere.

The most difficult part — that of the antibodies — is already filled. They were discovered — actually created — by Rittenhouse-Olson in her lab nearly 20 years ago, by cloning a mouse spleen cell with a mouse tumor cell.

“It got its immortality from the tumor cell and the antibody from the mouse spleen cell,” she explains, keeping it simple.

She named the new antibody JAA-F11. That sounds like a fighter jet that shoots down tumors, but this microbiologist is more sentimental. She made the name from the initials of her three children, Jennifer, Anna and Andrew, combined with the grid location — F11 — in the culture plate where the antibody grew.

After her initial discovery, she has worked with students and her longtime research lab technician Susan Morey to reproduce the antibody and test its ability to stop cancer in its tracks, using mice as live subjects and human cells in Petri dishes. Now, they are “humanizing” the antibody, taking the mouse antibody binding ability and attaching it to human antibody molecules.

JAA-F11 bonds with the part of the cancer cell — a sugar, the Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen — that helps it move through the bloodstream. Once JAA-F11 attaches, the antigen doesn’t work and the cancer doesn’t spread.

It has proven to be remarkably effective.

Now, JAA-F11 is taking its first major steps in front of a wider audience. Rittenhouse-Olson has started a company to develop a marketable cancer therapy and already has early interest from several major pharmaceutical companies.

She has been awarded hundreds of thousands of dollars from the National Cancer Institute and University at Buffalo to begin the next phase of testing on her breakthrough, which is a few steps ahead of human trials.

“We aren’t all the way there, but it shows real promise,” Rittenhouse-Olson said.